Why we work

We work around 90,000 hours in our life time. This is about one third of our lives. Some people are chronic workaholics and others clinically-diagnosed unemployed. One way or another, on average we spend tremendous energy and time working for money. Money has become a life and death matter: We need to buy a roof over our heads, food to munch, and water to drink. Certainly we need things, and later we want things.

In this nihilistic Finnish economy, we do not have the luxury to choose work that pays adequately. Sometimes we do not even have the option to receive work that matches your skills, interests, and professional background. We need to do whatever work is available to meet our ends. (Or marry someone wealthy.) And those who earn money barely have enough to save; their money goes directly from one hand to multiple smaller mouths.

And even if all was fine and dandy and we had typical working hours in a normal corporate structure, we are usually not granted the right to work less than needed for smaller pay. But we can choose not to use as much money as we do and instead save. But that is difficult. Very difficult. Consuming is enticing and it is a habit difficult to get out of. Moreover, consuming and buying more and more provides temporary satisfaction and relief after all those sweaty working hours. “I deserve it” I tell myself.

Either way, money as we are told, is necessary for living, and therefore we must work. But if the thing we work for is intentionally designed to be against you, meaning that the money you earn depreciates faster than your salary keeps apace, then it would be crucial to understand what the heck we are actually doing every day, by habit, unaware. Maybe we can do something about this?

Even more important is the tangible experience of all of this. I mean that when you are a kid, you do not have to work, think how to earn money, how debt works, or what to invest into. I believe this is good for the young child to have an innocent childhood. But the dad who tells the kid that “all money is debt” – without the kid having to experience 9-5 working, acquiring capital assets, and then getting into debt – is only half-way there.

This is to say that one does not arrive to the experiential knowledge of what 9-5 means and how money works until later in youth and adulthood. Experience of being in debt, earning money, sending money to a friend far abroad, counting your coins, paying something in the internet, going to a bank to get a loan and reading the fine print, and investing into technology stocks and index funds.

Relatedly, learning how bitcoin works or how code works, intellectually, without ever sending or receiving bitcoin or coding a program means very little to one’s true understanding.

Similarly, collecting rare physical Pokémon cards, acquiring unique and valuable virtual in-game items, or buying a piece of physical art is paramount to understanding how scarcity manifests through experience. If you never owned anything scarce that was competed and desired by others, then how would you ever understand the feeling that the scarce thing evoked in you?

As such, after understanding scarcity, money and work – not only rationally and intellectually from books, but also through experience through life circumstances – we arrive to a particular place. We need to be in this place in order to ask more deeper questions about money. We need to be in this place, because there we become aware and take the first step.

All this is to say that money is one of the most ubiquitous thing there is. We rarely, if at all, question it. We are told the false story that money is tied to happiness and we need more money to be happier. Yet how money works is not taught in schools and families despite it being almost equivalent to God to some. We worship it to the extent that we compare our stock portfolios and centre our lives around getting more. If we do this, then we ought to at least understand how money works.

Alas, we do not think how something works until it breaks. Be it your bicycle, your ego, or your money. When your bicycle breaks, you might start to wonder if you could fix it and learn bicycle mechanics. When your mind starts to develop mental impairments, you might start to self-reflect, wonder how to fix it, and learn more about yourself through therapy and insight (vipassana) meditation, or any other way, albeit quite late.

When money breaks, you begin to wonder how it works and how to avoid that.

Let’s go deeper. When you see rust on your bicycle, a pedal almost dropping, the back wheel wobbling, the gears rattling, and the breaks screeching, then you know you should have done the regular spring maintenance. Either way, the problem and the solution are quite obvious. But ego is a whole another construct.

Our minds constantly tell us stories that do not support our well-being. We trust it so much that some people believe even in the most heinous, amoral statements.

Even an enlightened person like the Buddha knew he had to remain skeptical. He learned to let go of every preconception the mind created about the reality it claimed was “it”. He kept observing diligently until he transcended mind and matter. Likewise, Jesus kept Satan at bay in the desert for forty days, and maintained his mind pure despite what Satan promised him. There was not even a trace of impurity nor sin in him, even during his crucifixion.

Then there is money. Living cozy and safe in Finland, money works relatively well. I have no complaints. For someone living in Venezuela though, it is a comedic tragedy involving wheel carts of worthless paper cash. These are two completely different experiential realities. Money is like the mind in the sense that the change is minimal, gradual, and quiet. This is why we may not be aware of it until it is too late.

When money breaks

What does it mean when money breaks? It is quite different respective to who is looking and from which angle. But for you and me, it means that you are no longer able to buy the same things as you used to with money.

This problem is as ancient as the money from Roman times with gold coins, aureus. Aureus was used from around 27 BCE until the 4th century, when solidus became the new dominant gold coin. Around and after the time of Jesus, Romans progressively reduced gold content in their coins over centuries, because of economic pressures. The vast militaristic empire expanded its borders through conquests, requiring more money to support its infrastructure and bureaucracy. Therefore, this gradual debasement meant that people paid attention quite slowly, especially when the coin’s physical appearance remained similar.

Two thousand years later we are still living the same way. While today we do not use gold coins, we have electronic money whose stable value is guaranteed by our governments. But governments change every four years, from left to right, to democracy to autocracy, and vice versa. Not only that, but also contemporary money is intentionally designed to inflate in order to stimulate the national economy to grow. As such, the value of money is bound to change accordingly, and together the goods and services increase in price.

What is money

I hate to break it to you but there are no paper bills or gold bars sitting in the Finnish bank vaults. Contemporary money is purely digital numbers in a ledger coordinated by banks and central banks. Certainly we also use paper money and metal coins, though this is only a fraction of what money is today.

Virtually all contemporary money is debt (Desjardins, 2020). Debt is a promise you owe to bank, which you are obliged to repay later with interest. Debt is an abstract social contract that has little to do with tangible objects like paper bills. It is a promise, and such a promise is possible because we have made rules upon rules upon rules that help us navigate those abstractions with rewards and punishments. It would be socially and financially costly to cheat and not pay your debts.

Because majority of money is debt, Finnish commercial banks are legally obliged to hold less than one percent of the overall money that they have (ECB, 2023). For the Americans banks it is zero percent (Fed, 2020). This is also by design. This means that if all Finns withdrew their money from their banks en masse, the banks would stop functioning and implode. Banks cannot hand out social contracts. This is called a “bank run” and it happens quite often during economic crises; I bet you didn’t know that. This is why debt is only possible to give when we enjoy trust toward other institutions who keep their word and protect us.

In terms of experience, we know that euros and dollars lose value because banks create new debt. There is nothing nefarious in that per se. The creation of new money is probably well-meant by certain economists.

But the problem is what kind of consequences it creates in the long term. For one person, it means that goods and services increase in price, which means they’re able to get less and less of them. This can create discomfort knowing that one’s lifestyle is slowly constricted. One is not able to own a house or to enjoy final years in decent elderly care. And who can we blame? There is no single person who is responsible for this. Secondly, it creates the constant pressure to beat inflation. This means that one is now personally responsible for taking financial risks in order to save their money in other assets, if one has the time and opportunity to even do that. Luckily we have Bitcoin.

What is Bitcoin

I have written a lot about Bitcoin. Therefore, I am not so much interested in opening it up here that much. What you need to know are we can observe about Bitcoin with genuine confidence (Giovani, StephenPerrenod, APSK32, PlanC, & Fred Krueger, 2024). Moreover, we also take a look what makes Bitcoin valuable, among other things.

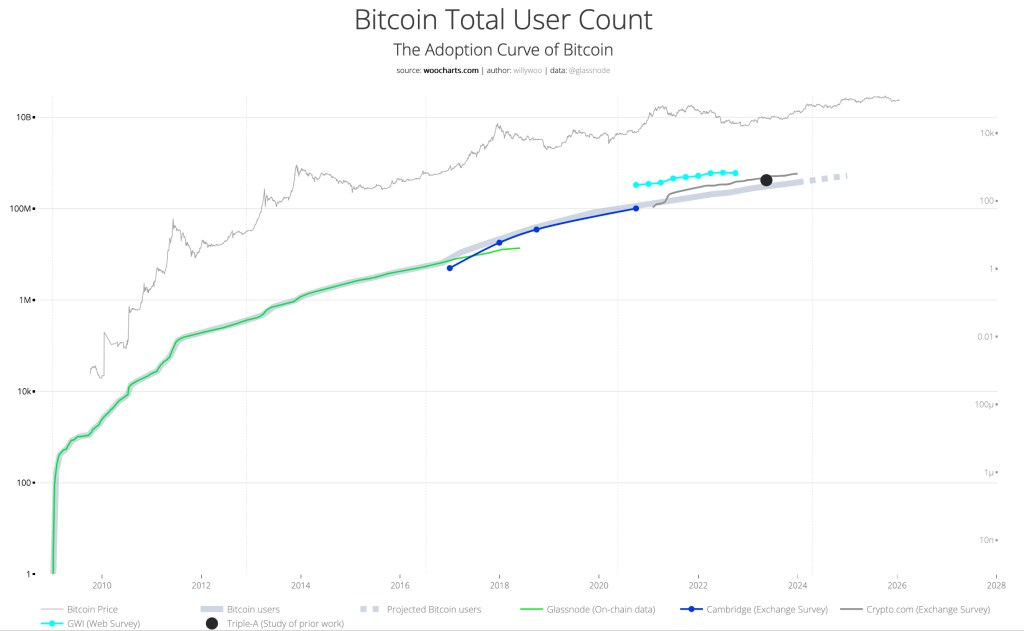

The first observable pattern is steady adoption. By counting addresses holding meaningful amounts, researchers have documented growth at a remarkably consistent pace, regardless whether markets are soaring or collapsing.

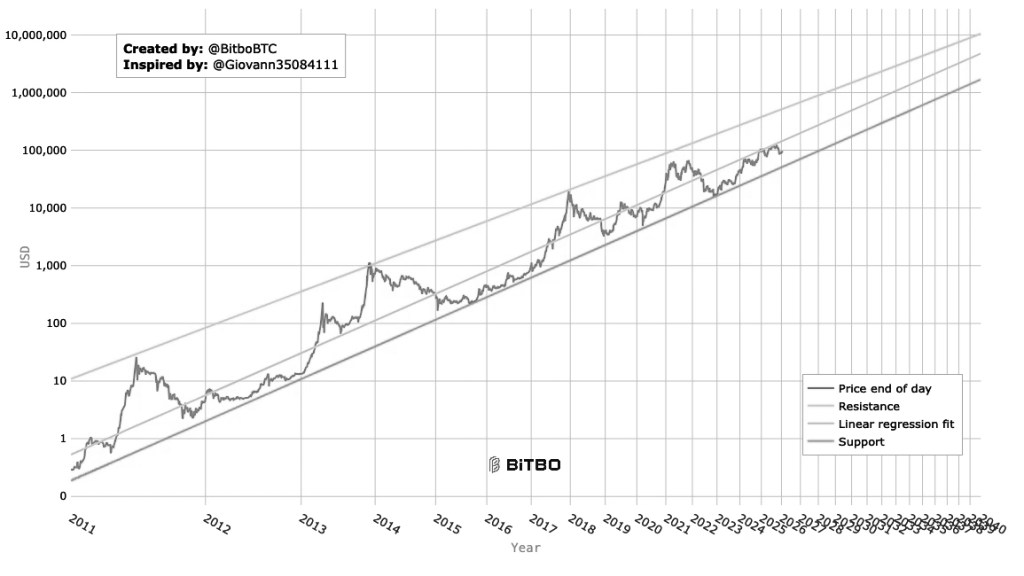

The second is a mathematical relationship between adoption, supply, and price that has proven surprisingly stable and modellable over time.

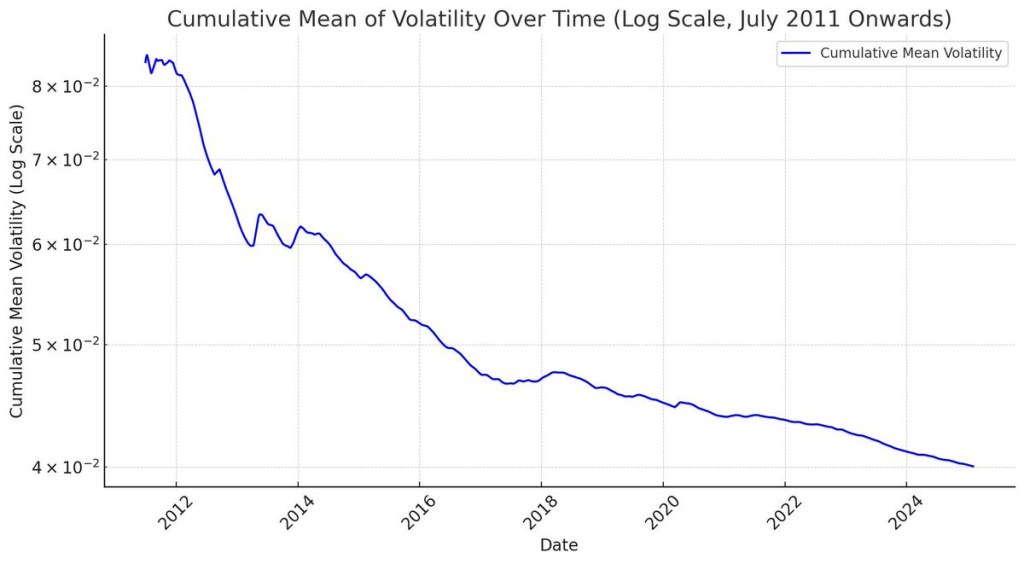

The third observation, perhaps most intriguing, is that Bitcoin has become progressively less volatile. The wild swings of earlier years have gradually smoothed as adoption has broadened, suggesting the emergence of an asset class with less extreme price movements, though volatility remains substantially higher than major fiat-currencies or gold.

The fourth pattern is that Bitcoin functions primarily as a medium for smaller transfers rather than large-value transactions (Auer, Lewrick & Paulick, 2025).

How scarce is Bitcoin

It is kind of weird to think that something digital could be scarce. Just copy and paste and there you go; no longer scarce but a duplicate. But Bitcoin is the first to succeed as a scarce thing that lives in the internet. But to do that, we need to expend energy. So, the price of one bitcoin is at least the price it takes to produce it, that is, how much energy it cost to “create” it.

When something is scarce, we talk about something being a “limited edition” or that “there are only a few left” (Gierl & Huettl, 2010). Indeed, by looking at the numbers objectively, we can observe that there is indeed one of this “thing” and ninety-nine of this “kind”. And depending on the context characterised by competition, I would choose the scarce “thing” instead the generic “kind”.

What we need to know is that something is scarce because there is little supply or there is a lot of demand. These are two sides of the same coin.

For example, there can be quite a lot of demand for ice scream depending on the season, and hence creating scarcity. This is how companies adjust their production depending on the demand even if they could provide more than necessary supply. Consequently, ice scream is not scarce by nature but quite abundant. But to make it look like it’s scarce for the perceiving observer, the company advertises ice scream as though it’s in high demand. We can see that ice scream can in no way be “a limited edition”, even if the seasonal ice scream varieties make it look like such.

Then there’s the crafty diamond mouthbreather producers. Prior to late nineteenth century, most of the diamonds came from India and Brazil. After that they found lots and lots of it in South Africa. So, the biggest investors in the diamond industry figured that they had no choice but to merge their interests into a monopoly. Doing so meant that they became powerful enough to constrict production and create the illusion that diamonds were scarce (Epstein, 1982). And they succeeded quite well at that too. This is called a cartel and a monopoly.

Then, the scarcity of diamonds here is not so much about demand but rather little supply. They knew there was consistent demand all over the world; they made sure of that by romanticising the idea of owning a diamond jewellery. Even if the diamond industry at that time did not create a cartel and control prices, objectively speaking there exists physically speaking only so much diamond on Earth. Doing so meant they could reap the profits over longer periods of time, instead of losing their profits because of sudden supply increase.

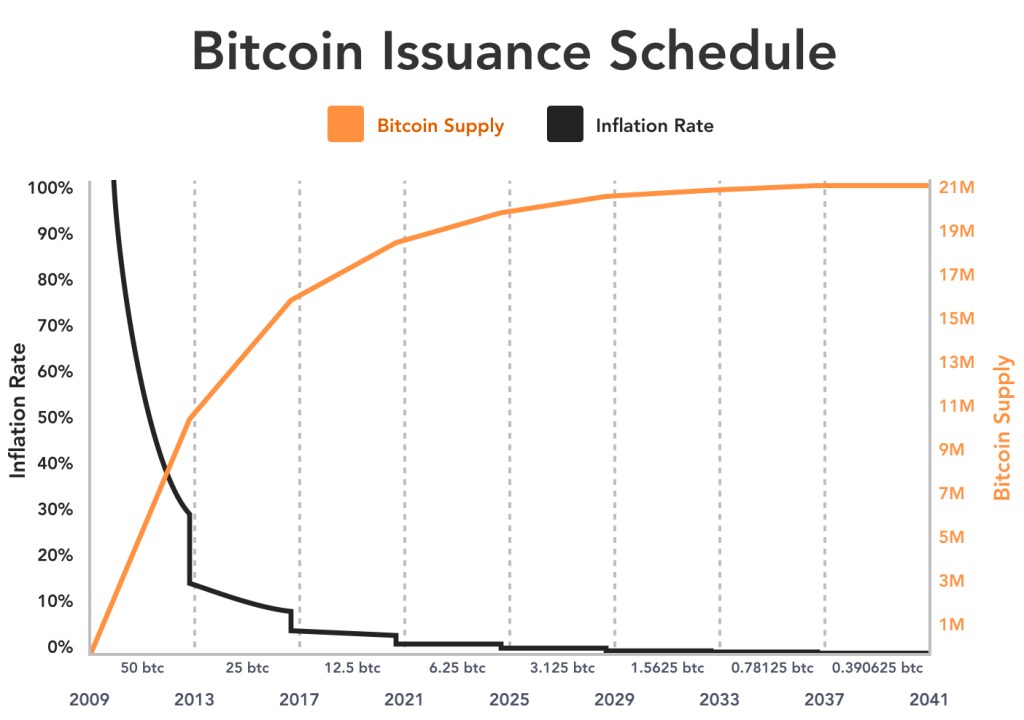

Then there’s Bitcoin. The maximum amount of bitcoin there will ever be one day is 21 million bitcoin or 2.1 quadrillion satoshis. One bitcoin can be divided into 100,000,000 satoshis, like one euro coin is a hundred cents. That alone does not say much because it could be any number. This is only to say that the supply of bitcoin is fixed and we know it beforehand. Compared to ice scream, diamonds, or euros; we do not know how much of it there will ever be because the supply is manipulated by the producer.

In contrast, the supply of bitcoin is not something that a company or a cartel can determine or manipulate, because Bitcoin is a rule-based system without rulers. Those who play fair with the rules will be rewarded in bitcoin for their participation, namely the participants who help maintain the security of the network as well as update who own what and how much bitcoin. Moreover, they along with other participants reify those rules, making it even harder to cheat.

The supply of new bitcoin in circulation is not affected by how much demand there is. This is how the rules simply work, and there is 16 years of evidence that this is how it goes, despite any contrary opinions.

I know that this is hard to comprehend. Simply it means that as demand grows steadily and goes through manic ups and downs and the supply of available bitcoin diminishes slowly, the price of bitcoin is bound to increase. Bound to increase.

What scarcity does

Anyone can think about any phenomenon using numbers or through stories. I would say stories and data both complement each other, although stories are more powerful and meaningful to humans than pure data. To demonstrate how six million Jews died in the Holocaust through real-life documentaries, monuments, museums, movies and books is an extremely powerful and emotional approach. Compare that to a table of numbers showing how many Jews died where, when, how, and so on in various columns and rows, it becomes dull, corporate, and bureaucratic. Although, one, there are those who make data look sexy, and two, data can tell much more in one quick glimpse than a long story. So there’s that too.

So what is scarcity anyway? Scarcity means that there is very little of something and in that particular context it may make sense to value it more than in other times. For example, drinkable water is abundant in Finland, but non-existent in the Sahara. There water is valued objectively more. Life itself and the moments we enjoy are scarce when we are reminded of death, making us value life more (King, Hicks & Abdelkhalik, 2009). This is something I have personally come in contact with in vipassana-meditation retreats and psilocybin mushroom trial, naturally without explicit reminders.

We begin to understand scarcity when we are six years old, and have preference for scarce goods in the presence of competitors (John, Melis, Read, Rossano & Tomasello, 2018). This was quite obvious when I was young and I kept all the rare legos to myself and only a few if any, to my younger brother.

However, children can recognise and respond to scarcity, but they do not spontaneously treat it as a desirable feature (Echelbarger & Gelman, 2017). Children notice when toys are plentiful or rare and they adjust their behaviour accordingly. For example, they share more when duplicates exist, they allocate preferentially based on perceived quality, and they respond to context-dependent factors like whether they are competing for resources. However, the research indicates that scarcity is not the sole motive in children’s economic decision-making.

Considering this, Bitcoin as a scarce thing does not make it valuable by itself. Instead, scarcity as a characteristic is merely instrumental to other factors, such as quality, utility, social signalling, and competitive advantage, that drive its preference and value.

What to conclude

So far I told you a particular narrative and it goes as follows.

We spend roughly one third of our lives working. We work for money, and money has become as essential as the air we breathe. Yet money, as it exists today, is not a tangible thing – it is merely a digital promise, a social contract enforced by institutions we trust. And because of the way money is designed to inflate, the purchasing power we gain from our labour diminishes steadily, quietly and imperceptibly, like rust forming on a bicycle we do not maintain.

Neither school nor our families teaches us how money works until we are already ensnared in its tragedy. By then, we are accustomed to the system and we accept its rules as natural and immutable. We accept that we must work harder and longer to earn more. We have internalised the mythology that money does not grow on trees. But that is false. Money is unlimited and it does not take effort, time and work to create. Not for banks. Like Buddha observing the monkey-mind, or Jesus resisting temptation in the desert, we ought to observe money with clear eyes and question the narratives we have been told.

Bitcoin is fundamentally different from the money we know. Its supply is fixed at 21 million bitcoin. It cannot be debased by governments changing every four years. It cannot be inflated at the whim of central banks and economists pursuing infinite growth. The rules are written into mathematics, and mathematics does not negotiate, does not lie and does not break its promises under political pressure.

As demand for Bitcoin grows – and it will grow, because more and more people are awakening to the realisation that their money is slowly losing value – and as the supply remains constrained by design, the price is bound to increase. Not perhaps. Not might. Bound to increase. This is merely the consequence of supply and demand, not financial advice.

Price aside, the principles behind Bitcoin are really what matters. For the first time in human history, we have money that is separated from politics. We have money that is not a promise backed up by faith and credit of a nation-state, but rather a system backed up by mathematics and distributed consensus. We have money that cannot be counterfeited, cannot be created at will, and cannot be seized from us by decree.

But still, for this to mean anything, you must experience it yourself. You must send bitcoin across the world and feel the immediacy of it. You must hold private keys and understand what it means to be your own bank. You must see your Bitcoin holdings increase in value over time, while continuing to research about monetary ethics, basic economics, technological adoption, politics and so on. Only then will you truly understand what it means to own something scarce in a world of infinite money. Only then will you grasp, not intellectually but also through experience, what money should be. Buy Bitcoin; Stack sats.

Afterword

The lovely person I asked to proofread this post told me to apologize to the readers for how long this post is. Sorry not sorry.

References

Auer, R., Lewrick, U., & Paulick, J. (2025). DeFiying gravity? An empirical analysis of cross-border Bitcoin, Ether and stablecoin flows. Monetary and Economic Department. Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/work1265.pdf

Desjardins, J. (2020). All of the World’s Money and Markets in One Visualization. Visual Capitalist. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/all-of-the-worlds-money-and-markets-in-one-visualization-2020/

European Central Bank (ECB). (2023). ECB adjusts remuneration of minimum reserves. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2023/html/ecb.pr230727~7206e9aa48.en.html

Echelbarger, M., & Gelman, S. A. (2017). The value of variety and scarcity across development. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 156, 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2016.11.010

Epstein, E. J. (1982, February). Have you ever tried to sell a diamond? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1982/02/have-you-ever-tried-to-sell-a-diamond/304575/

The Federal Reserve (Fed). (2020). Reserve Requirements. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/reservereq.htm

Gierl, H., & Huettl, V. (2010). Are scarce products always more attractive? The interaction of different types of scarcity signals with products’ suitability for conspicuous consumption. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 27(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.02.002

Giovani, StephenPerrenod, APSK32, PlanC, & Fred Krueger. (2024). The Big Picture. What we know with high probability about Bitcoin. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1dp2DGcCtmoILySeLBR9FEKYZAcKtCteQXNah1KXPE1A/edit?tab=t.0

John, M., Melis, A. P., Read, D., Rossano, F., & Tomasello, M. (2018). The preference for scarcity: A developmental and comparative perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 35(8), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21109

King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., & Abdelkhalik, J. (2009). Death, life, scarcity, and value: An alternative perspective on the meaning of death. Psychological Science, 20(12), 1459–1462. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02466.x

Leave a comment