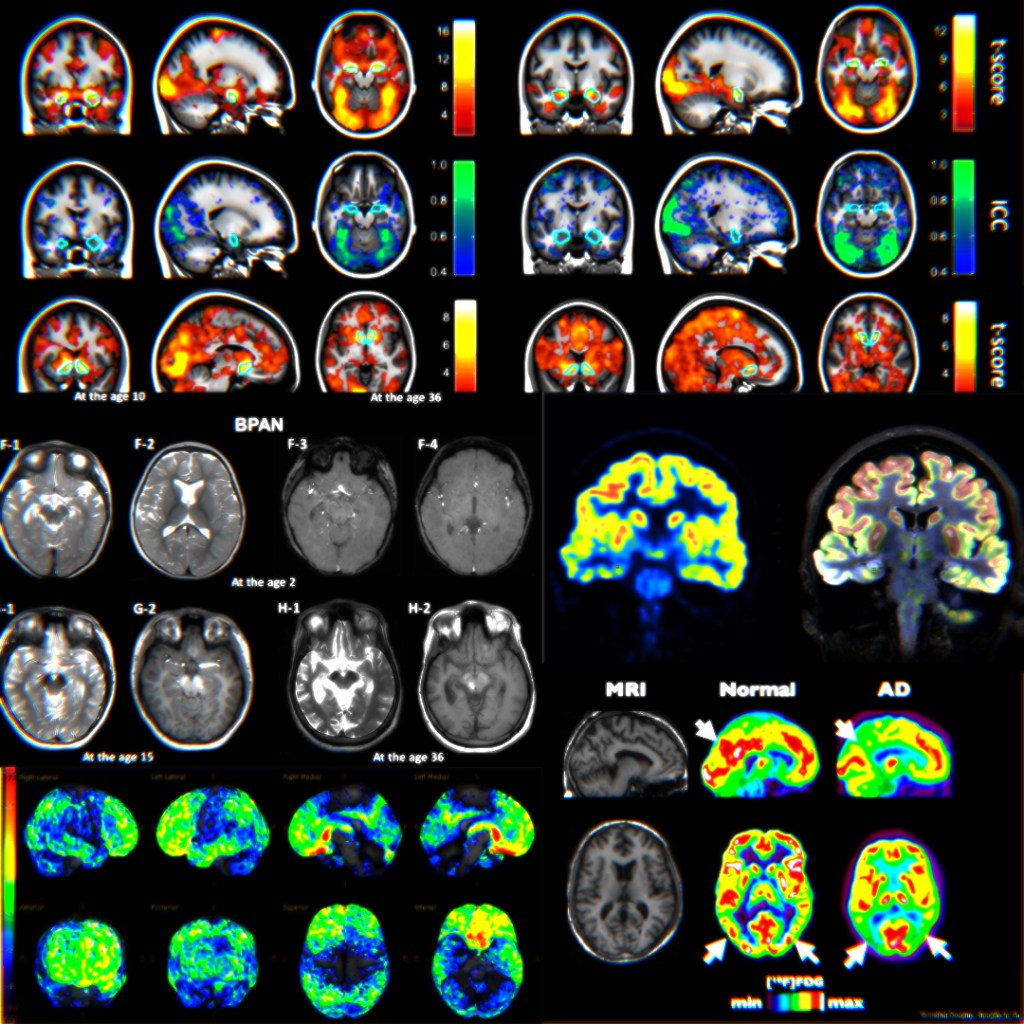

Here are some fMRI brain scans.

They could show the brain when shown a video of bullying. See how the colourful blobs light up? Red here, blue there, yellow scattered around here and there. The caption could say “Bullying causes an acute alarm state in the brain“.

It looks scientific. It looks important. But what does it actually tell you?

That brains do stuff when you see a video. Which, okay. Where else would the thinking happen? Your elbow?

My Problem

I studied neuroscience in the Netherlands for a while. Enough study credits to know what I was looking at. The main question being: what is all this for?

The brain scans are everywhere now. Pop science articles love them. TED talks flash them on screen while someone explains your brain on meditation, or music, or falling in love. They look so official. So undeniable. This is your brain. This is what it does. The science, has, spoken.

But most of the time, these scans are just confirming things we already knew from watching people. We know mothers and babies bond when they touch each other. We can see it happen. We can measure it with questionnaires and observations. Then neuroscience comes along and says “aha, and also oxytocin levels rise in the brain during this.”

Great. But did we learn anything new? Or did we just describe the same phenomenon with fancier words?

This is what I mean by glitter. It catches the eye, but it will not help you fix anything.

What The Scans Actually Show

Here is how an fMRI works. It measures blood flow in the brain. More blood flow means more activity. So when a brain region “lights up,” that means blood is rushing there. Something is happening.

But what, exactly?

Say you watch a first-person videos of bullying (victimisation) in the school environment. Say, your visual cortex activates. The scan shows this clearly. But was your brain responding to the movement on screen? The colours? The shapes? The emotional content? The narrative? All of the above? The scan cannot tell you. It just says “this general area got busy.”

To figure out what is actually happening, you need to break everything down into tiny pieces. Show the brain just movement. Then just colour. Then just texture. Test each thing separately. This works okay for vision research because you can control the inputs precisely. Show someone vertical lines. Then horizontal lines. Then diagonal lines. Eventually you map out which neurons respond to which features.

But what about love? What about depression? These experiences involve activity scattered across the whole brain. Multiple regions talking to each other in ways we barely understand. You cannot just show someone “pure love” and measure what happens. Love is not a vertical line.

Don’t even get me started with the problems of fMRI itself:

- It’s indirect. fMRI measures blood flow, not neurons firing. The BOLD signal is only a proxy, and the link between brain activity and blood response is messy (Logothetis, 2008).

- It’s slow. Neurons fire in milliseconds, but the blood flow response takes seconds. Fast events blur together (Kwong et al., 1992).

- It’s blurry. Each voxel covers millions of neurons. Blood vessels can shift the signal away from where the neurons actually fired (Friston, 2007).

- It’s inconsistent. The same person scanned on different days may show different patterns. Different people often light up in slightly different places even for the same task (Bennett & Miller, 2010).

- It struggles with comparisons. fMRI is decent at telling whether condition A vs condition B differs within one person. But comparing across people or predicting traits is much less reliable (Elliott et al., 2020).

- It’s noisy. Breathing, heartbeat, tiny head movements, scanner quirks—all of these mess with the signal (Logothetis, 2008).

- It’s expensive and uncomfortable. Huge machines, high running costs, noisy, claustrophobic tubes. Not everyone can do it, and the setting itself can change brain activity (Wellwisp, 2023).

- It forces trade-offs. If you try to get finer spatial detail, you lose signal strength. If you try faster timing, you also lose reliability (Lindquist, 2008).

- It only shows correlation. A region “lighting up” doesn’t mean it caused the thought or feeling. It’s just along for the ride (Poldrack, 2006).

- It has reproducibility problems. Different analysis choices can lead to different results, and repeating scans doesn’t always give the same answer (Botvinik-Nezer et al., 2020).

The Vocabulary Switch

Something interesting has happened in popular science writing over the last couple decades. It used to be all psychology terms. People talked about the ego and the unconscious and defense mechanisms. Now it is all neuroscience. People talk about dopamine and the prefrontal cortex and neural pathways.

Same conversations, different words. Before, science writers said “this makes you happy.” Now they say “this triggers dopamine release in the reward pathway.”

But has our actual understanding improved? Or have we just upgraded our vocabulary?

Psychology dealt with black boxes. You could not see inside someone’s mind, so you studied their behaviour and inferred what was happening internally. Neuroscience promised to open those black boxes and show us the machinery.

And to some extent it has. We know more about how neurons communicate. How networks form. How different brain areas specialise. But in a lot of ways we just created smaller black boxes. Instead of saying “this person has depression,” we say “this person shows altered activity in the prefrontal cortex and reduced serotonin signalling.”

Which sounds more scientific. But have we actually explained depression? Or just described it at a different level?

What Works

Okay, neuroscience is not completely useless. Some of it is genuinely important.

Brain computer interfaces that let paralysed people control robotic limbs. That is real. That helps people. Understanding how synapses work has led to better medications for epilepsy and Parkinson’s. That matters. Figuring out which brain areas handle language has helped surgeons avoid damaging them during tumour removals.

These applications share something in common. They are specific. They have clear goals. They test precise mechanisms and build concrete solutions.

The problem is the other kind of neuroscience. The correlational kind. The kind that says “we scanned people’s brains while they looked at attractive faces and found activation in these areas.” Okay. And then what? What do we do with that information?

Some researchers argue this groundwork is necessary. You have to map the territory before you can navigate it. You need the basic correlations before you can understand the mechanisms. Maybe in fifty years I will look back and say “oh, those early fMRI studies were crude but essential.”

Maybe. But it is also possible we are just generating expensive data that confirms common sense observations. Which would make it decorative knowledge. Knowledge that looks impressive but does not build anything.

The Measurement Problem

Here is another issue. Psychology has always struggled with measurement. How do you measure personality? Or intelligence? Or happiness? You give people questionnaires. You watch their behaviour. You ask them to rate things on scales from one to ten.

This feels squishy. Subjective. Neuroscience seems more objective. Neurons either fire or they do not. Blood either flows or it does not. The measurements are physical.

But the interpretation is still squishy. Say you find that a certain brain region activates when people report feeling anxious. Does that mean you have found the location of anxiety? Or just one brain area involved in a complex process that involves dozens of regions? And if different people’s anxiety involves slightly different patterns of activation, what does that mean?

We like to think brain scans show us ground truth. But they show us correlations. Association. This happens when that happens. Causation is harder to nail down.

And even when we find consistent neural correlates of something, we still need psychology to interpret what that something is. A neuron firing is not inherently “about” anything. It only means something when we connect it to behaviour and experience. You cannot eliminate the psychological level of description even if you understand all the neural details.

Where This Leaves Us

I do not think neuroscience is worthless. The specific, mechanistic research that breaks down processes into testable components has real value. So does research aimed at clear practical applications.

But the broad correlational studies that just say “brains do things when people do things” often feel like expensive ways to confirm the obvious. They produce impressive looking images and technical sounding papers. But they do not actually advance understanding in meaningful ways.

The field needs a clearer sense of purpose. What questions are actually worth asking? What kind of knowledge are we trying to build? What problems are we trying to solve?

Right now a lot of neuroscience feels like glitter. Pretty to look at. Catches the light nicely. Makes things seem more official and scientific. But ultimately decorative.

Maybe I am wrong. Maybe I missed something important during my studies. Maybe those correlational studies are building toward something that will make sense later.

Or maybe we are just dazzled by the pretty pictures. By the authority of brain scans and technical language. By the feeling that we are finally seeing the machinery of the mind, when really we are just seeing our own assumptions reflected back at us in fancier packaging.

Either way, the glitter keeps selling. And the research keeps getting funded. And the brain scans keep showing up in magazine articles promising to reveal the neural basis of everything.

Leave a comment