Winning a war isn’t enough. The real victory comes when you erase the defeated culture and replace it with your own. The second war happens after the first—and it’s fought with monuments, language, and memory instead of weapons.

The goal isn’t just territorial control but something deeper: to make Ukraine forget it was ever Ukrainian. I remember how Ukraine in their then Twitter account posted a lot of Ukrainian memories to fight against the Russian disinformation before the invasion. This was a way to recall Ukrainian identity amid disinformation attempts.

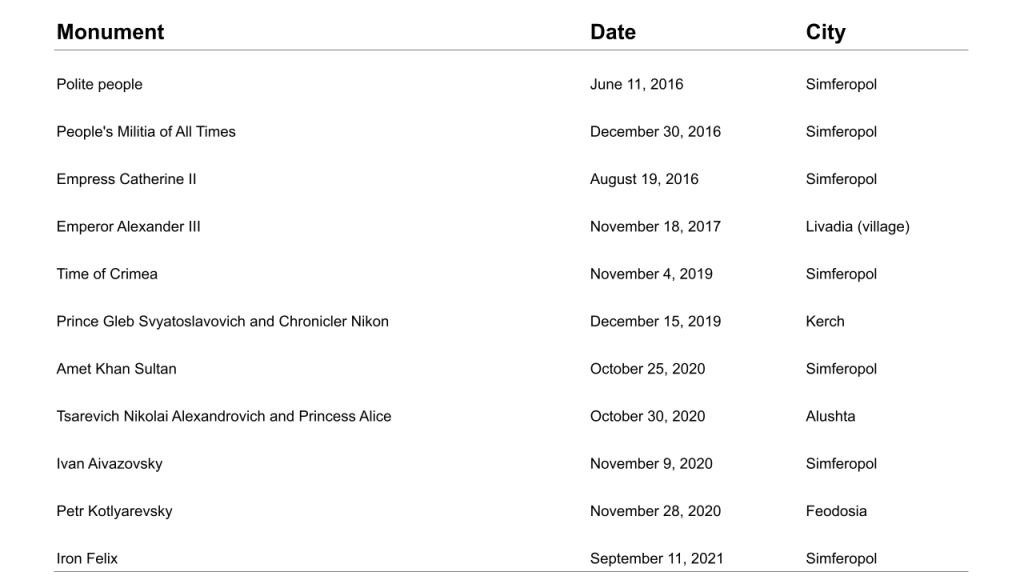

Figure 1. Monuments Built in Crimea Since Annexation 2014-2023

Russian elite want to get rid of Ukrainian heritage and culture, and put Russian architecture and memories, so that the inherent identity of Ukraine is destroyed and merged into Russia. Then, and only then, Russia has won the war.

Figure 2. Locations of Monuments in Crimea Since Annexation Between 2014-2023

Monuments and Identity

Monuments are not just big pieces of stone; they are also, in a sense, stories. You build one to say: this history happened here, this culture belongs here, therefore we belong here. Russia put up monuments in Crimea, not because people really need another statue, but because the statue itself quietly asserts: Crimea is Russia. And once it’s there, it nudges people’s sense of who they are—less uniquely Crimean, more broadly Russian.

Identity is always a jigsaw puzzle anyway: family stories, national myths, religion, work, class. This is what we studied in Peace and Memory course in Master’s programme.

Parents tell you their version of the past, the state offers another version, and somewhere in between you build your memory of who you are. The problem, of course, is when those versions collide. A Crimean monument might reinforce one person’s sense of Russianness while undermining another’s sense of being Ukrainian. So the monument becomes less about history itself and more about whose history gets to stand in the market square.

And while the state’s goal is to project one story and erase another, people don’t always read monuments the way elites intend as argued by Forest and Johnson, and Bellentani and Panico. Statues can mean loyalty or resentment, or maybe just a good place for pigeons, depending on who’s looking.

Violence and Nonviolence

The statue itself is not violent; but the act of putting it up, in disputed territory, carries a kind of cultural aggression. It says: our narrative wins, yours loses. That gesture can deepen divides and legitimise further conflict.

There is another option. Thinkers like Gandhi or Gene Sharp suggested that nonviolence—truth-telling, creative protest, stubborn refusal to cooperate—can undo oppressive systems more effectively than smashing things.

And statistically, the research backs this up: Erica Chenoweth’s work shows that nonviolent resistance movements succeed about twice as often as violent ones, in part because they can draw broader participation and don’t give the state an excuse to escalate repression. In the big picture, civil resistance works better than armed resistance, even if it’s slower, less viscerally satisfying, and more difficult.

Ukraine doesn’t have to blow up Russia’s monuments to resist their story; They can re-frame it instead.

After wars end, countries often choose different paths: some monuments get absorbed into new national pride, their original meanings conveniently forgotten, like how Napoleon’s Arc de Triomphe, built to celebrate empire, now honours all French war dead. Some get torn down in cathartic moments of liberation, like Saddam Hussein’s statue pulled down in Baghdad, though notably by the US Marines more than spontaneous crowds.

Others become contested sites where everyone argues forever, like Spain’s Valley of the Fallen, Franco’s monument-mausoleum that remains bitterly divisive decades after his death. And many others are simply forgotten, weeds growing around the pedestal, the hero’s name weathered illegible, until no one quite remembers why it’s there.

A nonviolent strategy is to let the monument stand but strip it of its intended power. Turn it into art, irony, memory, or something broader than the narrative it was built to enforce.

Lithuanians did this brilliantly with their Soviet sculptures, not destroying them but moving them to Grūtas Park, where Lenin and Stalin stand in a forest surrounded by explanatory plaques about Soviet repression. The statues lost their power once they were removed from town squares and placed in context. Visitors can see them, learn from them, even mock them—but they no longer dominate public space with an unquestioned narrative.

In that way the stone stays, but the meaning shifts—and what was once a tool of division becomes, potentially, part of reconciliation.

The broken arch in Kyiv does exactly this: it preserves the physical evidence of the Soviet narrative while simultaneously rejecting it. The break is honest. It doesn’t pretend the friendship was real, but it doesn’t pretend the past didn’t happen either. It’s a monument to the end of an illusion, which is its own kind of truth-telling.

And perhaps that’s the deepest form of nonviolent resistance: not destroying your enemy’s story, but standing beside it with your own, insisting that both be visible, that history be complicated rather than simple, that memory include the uncomfortable parts.

War is also fought with monuments and memory, yes, but it doesn’t have to be won through erasure like wars tend to be. Sometimes the most powerful statement is acknowledging the battle itself, leaving the scars visible, and choosing to interpret them differently than the people who inflicted them intended.

This work was produced through group effort in Vilnius, back in 2023.

Leave a comment